Here is a link to the original story on the team's website.

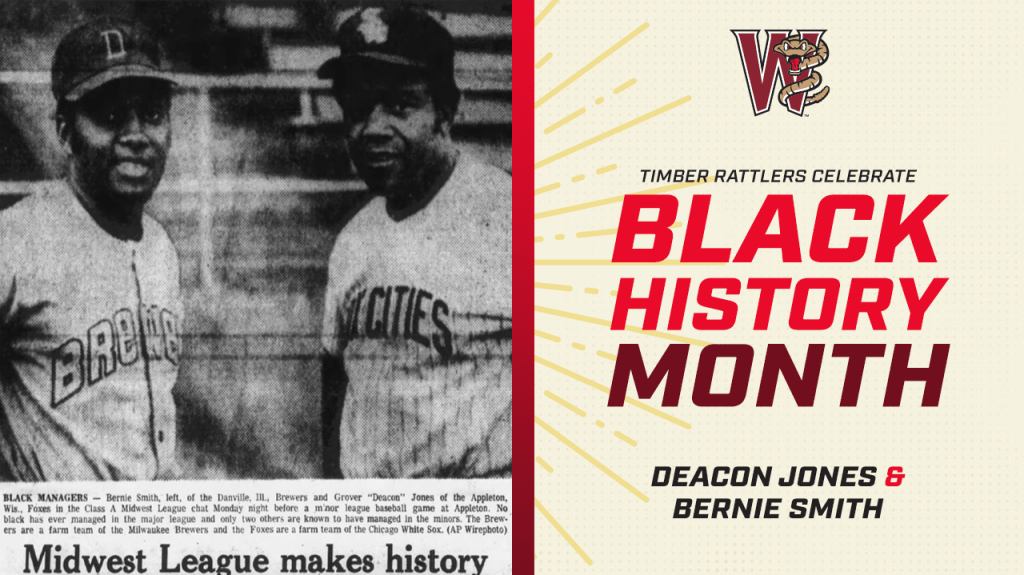

The Wisconsin Timber Rattlers continue Minor League Baseball’s celebration of Black History Month with a pair of history making minor league managers.

The Wisconsin Timber Rattlers continue Minor League Baseball’s celebration of Black History Month with a pair of history making minor league managers.

The Danville Warriors rallied from a 7-2 deficit to defeat the Appleton Foxes 10-7 in a game at Danville Stadium on April 25, 1973. The Warriors scored four runs in the seventh and four runs in the eighth to score a comeback win in front of 619 fans.

Those are the game details for what would seem to be a routine Midwest League game in 1973. There is a story behind those details to make this game historic for baseball and it happened in a small city two and a half hours south of Chicago and located just west of the Indiana border.

Grover “Deacon” Jones was the manager of the Foxes. Bernie Smith was the manager of the Warriors. They were the first African-America managers in the Midwest League and April 25, 1973 was the first game played in MiLB history where Black skippers led both teams.

There wasn’t much fanfare for the first game. That was not the case when the Foxes hosted the Warriors from May 19-21 at Goodland Field.

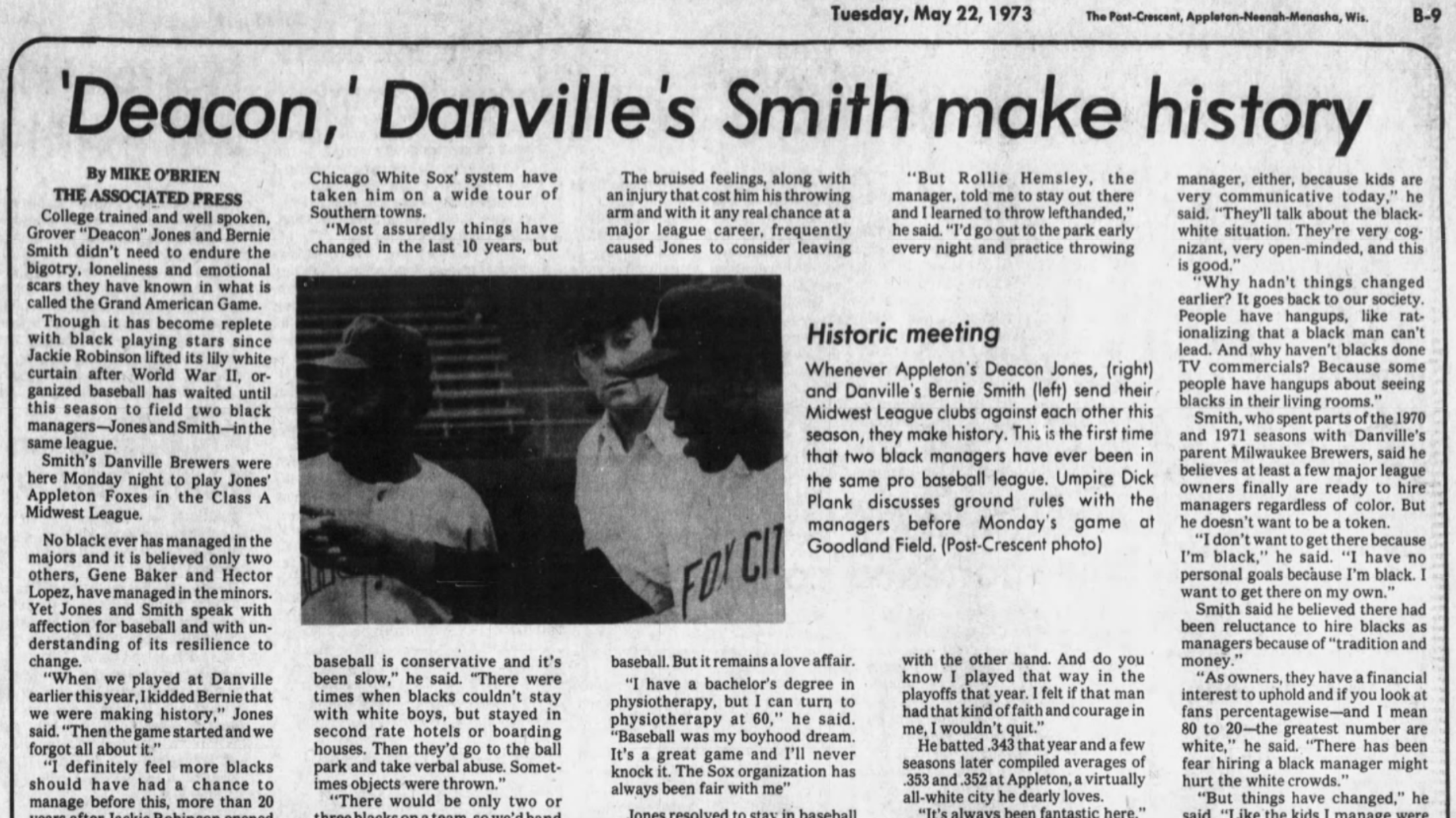

Associated Press sent writer Mike O’Brien to the Fox Cities for the final game of the series. His article gets the thoughts of both Jones and Smith to share with newspapers from Maine to Washington and from Wisconsin to Mississippi.

Smith’s Danville Brewers were here Monday night to play Jones Appleton Foxes is in the Class A Midwest league.

No Black has ever managed in the majors and it is believed only two others, Jean Baker and Hector Lopez, have managed in the minors. Yet Jones and Smith speak with affection for baseball and with understanding of its resistance to change.

“When we played at Danville earlier this year, I kidded Bernie that we were making history,” Jones said. “Then the game started and we forgot all about it.”

“I definitely feel more Blacks should have had a chance to manage before this, more than 20 years after Jackie Robinson opened the gates as a player and took a lot of abuse,” Jones said.

Jones later shared a story about his love for baseball, the Chicago White Sox, and the city of Appleton.

“I have a bachelor’s degree in physiotherapy, but I can turn to physiotherapy at 60,” he said. “Baseball was my boyhood dream. It’s a great game and I’ll never knock it. The Sox organization has always been fair with me.”

Jones resolved to stay in baseball after an incident that almost forced him out in 1963. Playing first base for Indianapolis, Jones couldn’t complete a throw to the plate because of intense pain in his right arm. It cost a game and he was near tears later.

“Rollie Hemsley, the manager, told me to stay out there and I learned to throw left-handed,” he said. “I’d go out to the park early every night and practice throwing with the other hand. And do you know I played that way in the playoffs that year. I felt that if that man had that kind of faith and courage in me, I wouldn’t quit.”

He batted .343 that year and a few seasons later compiled averages of .353 and .352 at Appleton, a virtually all-white city he dearly loves.

“It’s always been fantastic here,” he said. “When we first came, my wife said she felt like she was on stage, with people turning their heads to look at us. But that’s a natural reaction. We’ve made intimate friends here.”

Bernie Smith was officially the first African-American manager in the Midwest League due to being announced a few days before Jones.

Smith, a Louisiana native and a college teammate of Lou Brock at Southern University, spent years in the New York Mets system, including winning the Eastern League MVP in 1967 when he hit .306, stole 22 bases, and struck out just 47 times in 451 plate appearances for Williamsport. He got his chance in the Majors with Milwaukee and was a Brewer player in 1970 and 1971 for a total of 59 games before joining the minor league coaching staff for 1972 and getting the call to manage Danville in 1973.

Smith’s comments to O’Brien are about why it took so long for baseball to hire an African-American manager.

Smith said he believed there had been reluctance to hire Blacks as manager because of “tradition and money.”

“As owners, they have a financial interest to uphold and if you look at fans percentage-wise – and I mean 80 to 20 – the greatest number are white,” he said. “There has been fear hiring a Black manager might hurt the white crowds.”

“But things have changed,” he said. “Like the kids I manage were brought up in mixed schools, so they think nothing of it to have a Black as a coach. They don’t even think about it unless it’s pointed out.”

The series at Goodland Field went to Jones and the Foxes as they won game one 1-0 and game two 5-3. Danville won the finale 6-4 in eleven innings on the Monday evening that Mike O’Brien attended.

There would be three more matchups between Jones and Smith in 1973. The Foxes would again win two of the three games in the series when Danville hosted Appleton on June 6 and June 7. The teams split a doubleheader the first night with the Foxes taking the finale with a 6-0 win.

Smith would lead the Warriors to a 66-57 record and the playoffs with a win over Decatur in the first round, but a loss to Wisconsin Rapids in the Finals. Smith never managed in the minors again and his story of life after baseball is covered in more depth at this link at Reflections on Baseball by Steve Contursi.

Jones was reassigned as a hitting coach in the White Sox organization on June 20, 1973 after a loss to Wisconsin Rapids at home left Appleton with a 14-38 record. Deacon and the Foxes could never dig all the way out of the hole after starting the season with fifteen straight losses and a 1-19 record in their first twenty games.

The Post-Crescent made sure to include this passage in their article announcing the managerial change.

Jones’s next assignment will be the Knoxville Double-A club, where Lamar Johnson and Fred Norton are having hitting problems.

Though the White Sox announcement made no mention of the Foxes’ last place record, observers here felt that it played a large part in the reassignment decision. Jones, one of the most popular figures in Foxes history, wasn’t blamed by area fans for the team’s poor record since fox is personnel hasn’t been up to usual White Sox standards. There has been a constant shuffling of players on and off the roster, and several key injuries have also handicapped the team.

Jones, like Smith, would never manage again. However, Jones would stay in baseball. He would continue to coach in the White Sox system before moving on to become an advance scout for the Baltimore Orioles for over twenty years.

If you would like to more about Grover “Deacon” Jones, click this link for his SABR Biography by Bill Nowlin for stories like the night Jones sat at a rest stop lunch counter only to have a gun pulled on him and a different night when Virginia, Deacon’s wife, and Alicia Buford, wife of Don Buford, decided they weren’t going to sit in the segregated seating area at the stadium in Savannah in 1962.

It would take just over one year from the end of the 1973 Midwest League Finals for Major League Baseball to hire their first African-American manager. Frank Robinson, who had been traded to Cleveland from the California Angels during the 1974 season, was hired by the Indians on October 3, 1974 to take over as their player-manager for 1975.

#OTD in 1974: Frank Robinson agrees to become baseball’s first black manager, w/the Tribe.http://t.co/yc6Ot8c7j4 pic.twitter.com/rCMzB9TWv8

— Cleveland Guardians (@CleGuardians) October 3, 2015

Previous Articles for Black History Month 2022: